Review of Captain America: The Winter Soldier

/ Today my family and some friends made an event out of watching the first Captain America movie (well, the most recent reboot. Please forget this one. And this one. And this one.) and then going to see Captain America: The Winter Soldier. I won’t spoil the new one, but I can confidently say it was better than the first and worth your time.

Today my family and some friends made an event out of watching the first Captain America movie (well, the most recent reboot. Please forget this one. And this one. And this one.) and then going to see Captain America: The Winter Soldier. I won’t spoil the new one, but I can confidently say it was better than the first and worth your time.

First, let’s revel in the fact that Chris Evans is one of the best miscastings of all times. His turn as Steve Rogers (Captain America) has not only made him very successful, but it’s had some surprise bonuses. For one thing, it’s redeemed his performance as The Human Torch in those painful Fantastic Four movies. I thought he was some Hollywood douchebag in those. Watching his Steve Rogers, I realize he was channeling something very real about Johnny Storm’s character: He was a douchebag. I would not have been surprised if the first actor to be cast as two different superheroes had been a woman. There tend to be a smaller pool of Hollywood “it” girls, while Hollywood treats its myriad wooden

First, let’s revel in the fact that Chris Evans is one of the best miscastings of all times. His turn as Steve Rogers (Captain America) has not only made him very successful, but it’s had some surprise bonuses. For one thing, it’s redeemed his performance as The Human Torch in those painful Fantastic Four movies. I thought he was some Hollywood douchebag in those. Watching his Steve Rogers, I realize he was channeling something very real about Johnny Storm’s character: He was a douchebag. I would not have been surprised if the first actor to be cast as two different superheroes had been a woman. There tend to be a smaller pool of Hollywood “it” girls, while Hollywood treats its myriad wooden  action-hero-types as interchangeable. The female characters in comic books almost always have the same body types, specifically ones no human woman possesses, so I expected Hollywood to find the closest woman to that vision and toss her all the female roles. When I first heard they were casting The Human Torch as Captain America, I thought they were making that mistake, which seemed to be more progressive than I’d expected but still an error. It turns out that this new role allowed Chis Evans to show he has some range. While Evans’ Human Torch was all feigned swagger on top of a layer of insecure human on top of a core of genuine but uninteresting heroism, Evans’ Captain America in anything but. He’s always throwing himself on grenades, tossing himself between gunman and their targets, leaping before he looks in order to save the day. His layer of uninteresting hero is on the surface. He clearly gets that part of the comic book’s character. The reason Chris Evans is miscast is that Steve Rodgers is a fundamentally boring character in the comic books, and I’m sure they could have found someone with an even more square jaw and crazy muscles to play the part in that boring way. (If anything, Evans is too buff for Steve Rogers, who wasn’t the most roided-out of all the characters in the Marvel Universe.) Instead, they picked an

action-hero-types as interchangeable. The female characters in comic books almost always have the same body types, specifically ones no human woman possesses, so I expected Hollywood to find the closest woman to that vision and toss her all the female roles. When I first heard they were casting The Human Torch as Captain America, I thought they were making that mistake, which seemed to be more progressive than I’d expected but still an error. It turns out that this new role allowed Chis Evans to show he has some range. While Evans’ Human Torch was all feigned swagger on top of a layer of insecure human on top of a core of genuine but uninteresting heroism, Evans’ Captain America in anything but. He’s always throwing himself on grenades, tossing himself between gunman and their targets, leaping before he looks in order to save the day. His layer of uninteresting hero is on the surface. He clearly gets that part of the comic book’s character. The reason Chris Evans is miscast is that Steve Rodgers is a fundamentally boring character in the comic books, and I’m sure they could have found someone with an even more square jaw and crazy muscles to play the part in that boring way. (If anything, Evans is too buff for Steve Rogers, who wasn’t the most roided-out of all the characters in the Marvel Universe.) Instead, they picked an

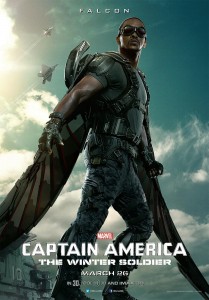

actor who can pull off a joke, something that was never particularly important in the Captain America comics. The Captain wasn’t the source of comic relief in the Avengers comics, either, but Evans can go toe-to-toe with actors with excellent comic timing in that franchise of films. In the original Captain America, he keeps up with Stanley Tucci and Tommy Lee Jones (the highlights of that film by far), and that’s quite an accomplishment. In this one, his banter with Anthony Mackie (Falcon)

actor who can pull off a joke, something that was never particularly important in the Captain America comics. The Captain wasn’t the source of comic relief in the Avengers comics, either, but Evans can go toe-to-toe with actors with excellent comic timing in that franchise of films. In the original Captain America, he keeps up with Stanley Tucci and Tommy Lee Jones (the highlights of that film by far), and that’s quite an accomplishment. In this one, his banter with Anthony Mackie (Falcon) and Scarlett Johansson (Black Widow) shows more wit than the comics’ Steve Rodgers ever had. But Evans’ ability to pull off a joke isn’t even the best thing about his mis-casting. It’s the fact that he was cast as much to play the before-Captain-America Steve Rogers as the after version. He maintains the courageous weakling that the first film chose to focus on so heavily, and that carries over into this movie even as his central conflict shifts to that of a man questioning his loyalties and assumptions about his place in the world. Essentially, Chris Evans (and a good script) give Steve Rogers more layers than the comic book’s Captain America ever had.

and Scarlett Johansson (Black Widow) shows more wit than the comics’ Steve Rodgers ever had. But Evans’ ability to pull off a joke isn’t even the best thing about his mis-casting. It’s the fact that he was cast as much to play the before-Captain-America Steve Rogers as the after version. He maintains the courageous weakling that the first film chose to focus on so heavily, and that carries over into this movie even as his central conflict shifts to that of a man questioning his loyalties and assumptions about his place in the world. Essentially, Chris Evans (and a good script) give Steve Rogers more layers than the comic book’s Captain America ever had.

The Winter Soldier does a good job of not going overboard with the characters’ angst or the allegory. It uses Steve Rogers’ return to the waking world after seventy years trapped in the ice as a nice parallel for the soldiers returning home from modern wars, though Anthony Mackie’s turn as Sam Wilson, a soldier returning from Iraq or Afghanistan, makes that metaphor a lot more believable and less forced. The movie resists the urge to dwell on this too much, especially since it could have confused the situation if they’d tried to contrast this struggle of Rogers’ and Wilson’s with the character of The Winter Soldier. I won’t give away too much about him, but it’snot a spoiler to say that The Winter Soldier is not an appropriate allegorical equivalent of a soldier struggling to come home from war or one tempted by the potentially lucrative benefits of becoming a mercenary, since it’s made explicitly clear that he is not really returning from a war and that he’s not a willful mercenary cashing in on his super-warrior skills. The Winter Soldier is something else, and if this movie took itself too seriously it might have inadvertently made some more bitter critiques of returning American soldiers than this light Hollywood fare would ever dare touch.

The Winter Soldier does a good job of not going overboard with the characters’ angst or the allegory. It uses Steve Rogers’ return to the waking world after seventy years trapped in the ice as a nice parallel for the soldiers returning home from modern wars, though Anthony Mackie’s turn as Sam Wilson, a soldier returning from Iraq or Afghanistan, makes that metaphor a lot more believable and less forced. The movie resists the urge to dwell on this too much, especially since it could have confused the situation if they’d tried to contrast this struggle of Rogers’ and Wilson’s with the character of The Winter Soldier. I won’t give away too much about him, but it’snot a spoiler to say that The Winter Soldier is not an appropriate allegorical equivalent of a soldier struggling to come home from war or one tempted by the potentially lucrative benefits of becoming a mercenary, since it’s made explicitly clear that he is not really returning from a war and that he’s not a willful mercenary cashing in on his super-warrior skills. The Winter Soldier is something else, and if this movie took itself too seriously it might have inadvertently made some more bitter critiques of returning American soldiers than this light Hollywood fare would ever dare touch.  If there is any sharp allegory, it’s not connected to the returning soldier plot-line, but to the danger of the surveillance state. Even that is subtle enough that no one at the NSA is worrying this movie will inspire a great public outcry. It was nice to see characters who held nuanced positions on the subject though, rather than good guys who uniformly support Freedom and bad guys who support Tyranny. Even the movie’s ultimate head villain is revealed to be someone who does not cackle or think of himself as evil, just a pragmatist who thinks he’s doing what it takes to make the world better. Comic book villains too often lack believable motives, and it was particularly satisfying that a number of the movies heroes occupied spaces between Captain America’s and the chief villains, and could articulate those positions in persuasively.

If there is any sharp allegory, it’s not connected to the returning soldier plot-line, but to the danger of the surveillance state. Even that is subtle enough that no one at the NSA is worrying this movie will inspire a great public outcry. It was nice to see characters who held nuanced positions on the subject though, rather than good guys who uniformly support Freedom and bad guys who support Tyranny. Even the movie’s ultimate head villain is revealed to be someone who does not cackle or think of himself as evil, just a pragmatist who thinks he’s doing what it takes to make the world better. Comic book villains too often lack believable motives, and it was particularly satisfying that a number of the movies heroes occupied spaces between Captain America’s and the chief villains, and could articulate those positions in persuasively.

Of course, mostly The Winter Soldier was about cars crashing and bullets ricocheting harmlessly but dramatically off of surfaces very close to the heroes’ faces. There was also a lot of acrobatic fighting, well-choreographed and better edited than the first. (While watching that one, my nine-year old son noticed that there was a hard cut between a shot of Captain America swinging on a chain and a shot of him running without any hint that he’d landed at some point in between. Noah theorized that it was a deleted scene in an extended edition, which is both nerd-dorable and more generous than calling it a mistake.) The body count in The Winter Soldier is both disturbingly high and unrealistically low considering the number of bullets flying and cars crashing into one another. An argument could be made about Hollywood’s desperate need to up the stakes always resulting in conflicts that threaten complete world-wide disaster, but, if that’s a problem (it is), comic book movies are not the place to start rectifying it. In the source material, the entire world is imperiled multiple times each month. At least in this movie, no major downtown areas are destroyed just to show that the bad guys are, in fact, dangerous.

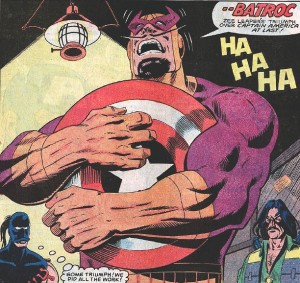

One last note from a comic book geek: It’s not a major spoiler to reveal that one of the villains in this movie is Batroc The Leaper, a character sometimes credited with being the lamest villain in the entire Marvel Universe. This movie did a great job of making him barely menacing and appropriately minor, a little shout-out to us old comic book fans that didn’t spoil the movie for people who are new to Captain America’s nemeses. I imagine that someone bet one of the screenwriters, Edward Brubaker, Stephen McFeely, or Christopher Marcus, that no one could ever get Batroc into a major motion picture, and that one of those gentlemen is now the proud owner of a crisp new five dollar bill. Well earned, sir!

One last note from a comic book geek: It’s not a major spoiler to reveal that one of the villains in this movie is Batroc The Leaper, a character sometimes credited with being the lamest villain in the entire Marvel Universe. This movie did a great job of making him barely menacing and appropriately minor, a little shout-out to us old comic book fans that didn’t spoil the movie for people who are new to Captain America’s nemeses. I imagine that someone bet one of the screenwriters, Edward Brubaker, Stephen McFeely, or Christopher Marcus, that no one could ever get Batroc into a major motion picture, and that one of those gentlemen is now the proud owner of a crisp new five dollar bill. Well earned, sir!