When We Can No Longer Relate: Creating Characters in an Age of Growing Economic Inequality

/ I was just reading a short story from Margaret Atwood's collection Moral Disorder titled "The Art of Cooking and Serving." To say the story was beautifully written is redundant; it was written by Margaret Atwood. In this particular story, an eleven year old tosses off a casual complaint about the fact that her parents' cabin doesn't have a refrigerator or a boat for water-skiing. It's not central to the story, but the detail suddenly kicked me out of the narrative and got me thinking about characterization and class. I expect that I am supposed to feel warmly toward the story's protagonist, but this small detail immediately makes me resent her. Her family can afford a second house but she complains about the amenities? I can barely afford one home which is far too cramped for my family, but we can't figure out how to get out from under it and into something more suitable. As an adult, I'm acutely aware that I am lower-middle class in my country (and very wealthy in relation to the majority of the people in the world). I don't think Atwood wanted me to resent the character (an 11 year-old, after all), but my class status makes this difficult. While I'm consciously aware that her childish reaction to the cabin is entirely realistic and understandable, and I can't reasonably expect an 11 year-old to count her blessings against the circumstances of others, I just have trouble relating to her. This one detail has made her feel distant. Not so much that I can't find other ways to connect to her and like her, but more than any single, small detail should affect my relationship to a character. And, as a writer, that has me worried.

I was just reading a short story from Margaret Atwood's collection Moral Disorder titled "The Art of Cooking and Serving." To say the story was beautifully written is redundant; it was written by Margaret Atwood. In this particular story, an eleven year old tosses off a casual complaint about the fact that her parents' cabin doesn't have a refrigerator or a boat for water-skiing. It's not central to the story, but the detail suddenly kicked me out of the narrative and got me thinking about characterization and class. I expect that I am supposed to feel warmly toward the story's protagonist, but this small detail immediately makes me resent her. Her family can afford a second house but she complains about the amenities? I can barely afford one home which is far too cramped for my family, but we can't figure out how to get out from under it and into something more suitable. As an adult, I'm acutely aware that I am lower-middle class in my country (and very wealthy in relation to the majority of the people in the world). I don't think Atwood wanted me to resent the character (an 11 year-old, after all), but my class status makes this difficult. While I'm consciously aware that her childish reaction to the cabin is entirely realistic and understandable, and I can't reasonably expect an 11 year-old to count her blessings against the circumstances of others, I just have trouble relating to her. This one detail has made her feel distant. Not so much that I can't find other ways to connect to her and like her, but more than any single, small detail should affect my relationship to a character. And, as a writer, that has me worried.

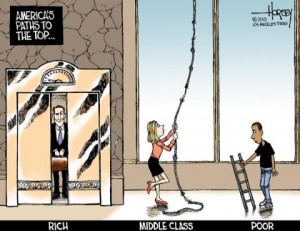

Not too long ago, Americans weren't even allowed to talk about class. The only people who spoke openly about it were the absolute dregs of our society; communists, artists, and academics. To even mention it, we were told, was to try to incite "class warfare." The forbidden nature of the subject didn't change the amount of money in anyone's bank accounts, but it did maintain the illusion of a cultural homogeneity longer than it would have lasted otherwise. At some point, the numbers told a story that all but the most ideological and willfully obtuse could not deny: The rich are getting dramatically richer. The poor are getting relatively poorer. The middle-class is thinning and fraying, like a rope pulled too tightly. There will come a point at which we have two distinct classes in America. There will come a point, at some unspecified time after that, when we acknowledge that fact. When it comes to social policy, I think it's all to the good that we are recognizing this change. Of course, it doesn't mean we can agree on solutions or even on whether it's a real problem. In our political climate, everyone has gone to their corners, of course. There's lots of talk about income inequality, and people are starting to talk openly about capital inequality now, too, though that's still pretty wonky. I could blather on it about it all day, but I won't. Rather than put forth policy proposals about changes to the tax code, as exciting as that would be for everyone, I think it's worthwhile for writers to consider what this will mean for us as we create characters.

Not too long ago, Americans weren't even allowed to talk about class. The only people who spoke openly about it were the absolute dregs of our society; communists, artists, and academics. To even mention it, we were told, was to try to incite "class warfare." The forbidden nature of the subject didn't change the amount of money in anyone's bank accounts, but it did maintain the illusion of a cultural homogeneity longer than it would have lasted otherwise. At some point, the numbers told a story that all but the most ideological and willfully obtuse could not deny: The rich are getting dramatically richer. The poor are getting relatively poorer. The middle-class is thinning and fraying, like a rope pulled too tightly. There will come a point at which we have two distinct classes in America. There will come a point, at some unspecified time after that, when we acknowledge that fact. When it comes to social policy, I think it's all to the good that we are recognizing this change. Of course, it doesn't mean we can agree on solutions or even on whether it's a real problem. In our political climate, everyone has gone to their corners, of course. There's lots of talk about income inequality, and people are starting to talk openly about capital inequality now, too, though that's still pretty wonky. I could blather on it about it all day, but I won't. Rather than put forth policy proposals about changes to the tax code, as exciting as that would be for everyone, I think it's worthwhile for writers to consider what this will mean for us as we create characters.

Once upon a time, people calmly accepted the fact that their societies were composed of haves and have-nots. In literature's ancient past, the characters were almost all haves; heroic warriors who were also kings, beautiful maidens who were also queens or princesses. When peasants were depicted at all, it was because they were on their way to becoming haves through pluck or twists of fate (and even then they were mostly haves who had been mistaken for have-nots and had to rediscover their true, noble station).

Readers rarely complained about the over-representation of wealthy characters in literature. That's because poor people couldn't read.

The middle class is a modern invention. The terms wasn't even coined until 1745, and even then it described a small but growing bourgeoisie population. Understandably, these mercantile city-dwellers didn't mind aspirational stories of middle class people becoming aristocrats, and they weren't turned off by stories that gave them glimpses into the lives of aristocrats themselves. As George Orwell pointed out, the middle class always wants to change places with the upper class. The upper class wants to stay where it is. Only the lower class wants equality, because they have the most to gain from it, so peasants might have wanted equality in the form of equal representation in literature, but again, they couldn't read.

Exporting education to the lower classes is an even more modern invention. In the 1800s, elementary education became available to the (slim) majority of children, and even then secondary and higher education remained closed off to most students due to sexism and racism. Still, though some would point out that correlation is not causation, I am a firm believer that it was the rise of free, public education that created the middle class in America.

Now we find ourselves regressing, and I wonder about the effect on literature. Once, when a writer wanted to write a story in which social class wasn't a significant theme, she could simply choose to make the characters middle class. Suddenly, it wasn't a story about poverty or wealth. The characters' class was still relevant, still defining in many ways, but it wasn't a signal to the reader that the character was too foreign to be relatable, or was deserving of pity, or was someone to admire or envy. The character had to earn pity or envy or admiration in other ways.

And this is what worries me. Sure, it's a small concern in the scope of the problems that will arise as income inequality grows, but it's an issue writers will have to wrestle with. If I create a character who complains about the condition of her second home, I need to worry about have-nots feeling what I feel toward Atwood's protagonist in "The Art of Cooking and Serving." Conversely, I don't know how a much wealthier reader might feel about one of my characters who is, say, searching through the Target circular on Thanksgiving night to go bargain hunting on Black Friday. Do very rich people know what that's like? Do they feel pity for people who have to clip coupons? Disgust? Condescending amusement? If the scene of a family going through those circulars was presented as joyous and warm, would a much wealthier person admire those poorer characters or envy their family bonding? I just don't know. I don't know what's it's like to be very rich. I can try to imagine it, but I can also imagine what it might be like to walk on the moon or swim with mermaids. That doesn't mean I'm good at predicting what real astronauts or real mermaids will identify with in my stories.

Once the middle class has essentially disappeared as a cultural group in the United States, will it even be possible to write characters without every story feeling like it's a story about class? Maybe that's fine. Maybe it's just a part of acknowledging something we should have been openly discussing all along. I'm very curious to see how writers (of novels, screenplays for TV and film, plays, etc.) handle the bifurcation of our society along economic lines. How are writers managing this question currently? How should they be?