Ben's New Study/Writer's Retreat/Super Villain Lair/Childhood Dream

/You may have had this experience when you were a child. Some adult gave you a piece of paper, probably that kind that has lines on the bottom half and a space to draw on the top half, and asked you to draw/describe your ideal house or bedroom. If you are like me, you drew a castle. With robots inside. And lots of guns and swords and bows and arrows. And maybe a water slide snaking in and out of the windows, and a system of tunnels allowing for easy entry and escape underneath the moat filled with sharks and alligators. The adult did not tell you you could never achieve this dream. He/she did not say, "Um, Ben, that's a dumb idea. The water slide looks structurally unsound. Alligators and sharks probably wouldn't live together like that. I'm a little disturbed by all the weapons. This is a childish fantasy, and you should really get over it as soon as possible." If the adult had said that, we would all think that adult is a jerk.

But the world does say that, and we all accept it. Or most of us do, anyway.

Not me. I say the world is a big fat jerk.

My family just bought a new house. It's nothing too grand, just a cookie-cutter house that's virtually indistinguishable from the other houses on the street. Seriously, we've discussed what kind of tasteful lawn ornamentation we can buy that will help us identify our own house without making the new neighbors think we're too weird.

Inside, I get to be weird. I now have my own study/writer's retreat/super villain lair, and it is a childhood dream come true.

Warning: Some of you may find the images that follow to be childish. That's because you have been given advice from somebody who accepted some variation of the Apostle Paul's decision to become a man and "put aside such childish things." Sucker! The joke is on you! Do you know Paul's life story? He spend his adult life first helping the Pharisees and the Romans persecute and kill Christians. Then he went blind for a while. Then he spent the rest of his life building Christian congregations, getting shipwrecked, heckled, tossed in jail, and writing letters until his previous employers had him executed. But you know what he did to support himself financially while he was building those congregations? He built tents. Do you know what a three-year-old calls it when he tosses a blanket over the couch and a chair? A fort. Now, Paul was a true believer, so I'll bet he didn't look back over his adult life and wish he could trade in all the letter-writing and shipwreck-surviving for more time building forts. I'm sure he was happy with his choices. Personally, I'm a skeptic, so the whole executing people and then being executed thing does not sound glorious to me. It sounds unpleasant. Building forts? Cool.

The purpose of this epistle is not to evangelize for extended childhood. It's to show off the room that makes my wife shake her head and wonder how she could end up stuck with a man who has gone bald and grown a gut but somehow managed to get less mature during their fifteen years of marriage.

I started with a room. It looked like this, but slightly bigger and in three dimensions:

Then I painted some lines on the walls.

And more lines. Then I added color to some of the spaces.

Then I did some sponge painting.

Yep. I made a castle.

Then some friends helped my bring in my bookshelves and boxes of books. (Thanks to my moving buddies!)

I populated the shelves.

My college friends will like this one.

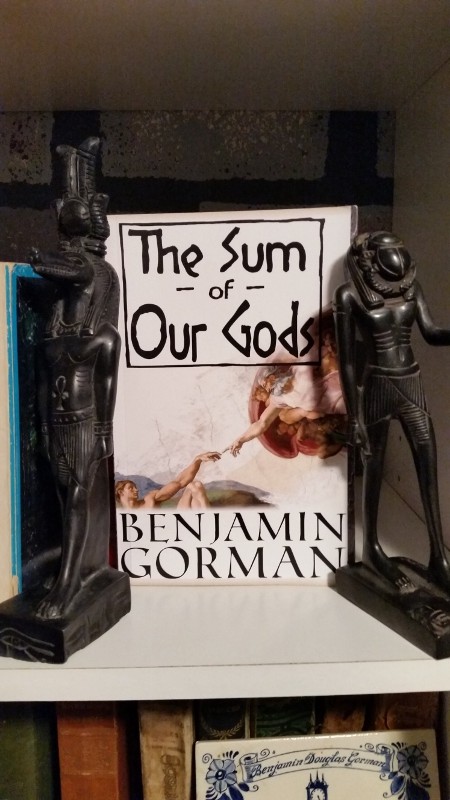

Here's my book with statues of a couple of the characters (the Egyptian gods Sobek and Khepri).

Here's a couple of my favs. Yoda. And Shakespeare. And Star Wars in Shakespeare's style.

I like turtles.

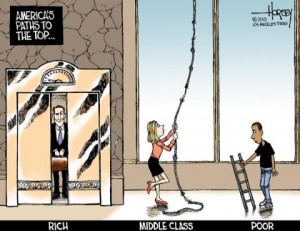

I think Virginia Wolf described this project succinctly.

Not pictured but included in the room: swords, bows and arrows, guns, and lots of toys.

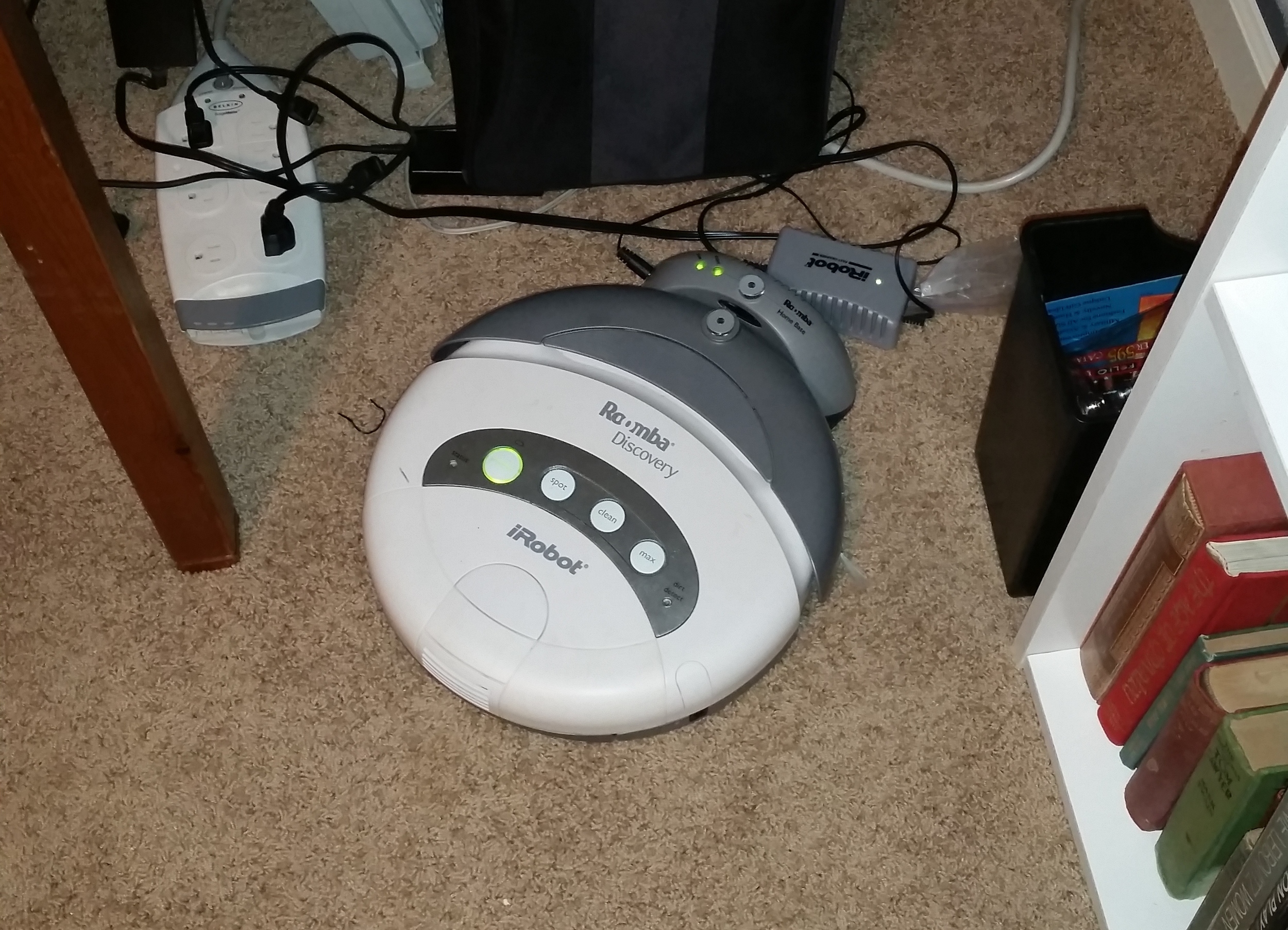

And yes, I do have a robot.

Is this room ridiculous and childish? Yep. And awesome. Should I put aside such childish things so I can be a normal soon-to-be-40 dad with a mini-van and a fantasy football team drowning his dead dreams in ironic Pabst? Nope. Should I get shipwrecked and tossed in jail and executed by Romans? Hell no! Adulthood blows. Build yourself a castle with a robot. Or whatever you wanted when you were 6. Because it's probably a whole lot more fun than what the world tells you to want now.

Now I'm going to go ask my wife if we can distinguish our cookie-cutter house by digging a trench, flooding it, and populating it with alligators and sharks. Just little ones. Classy, like a koi pond, but capable of repelling very small Visigoths. Wish me luck!